About nine-year-olds and Happy Birthday to Two Peds

Nine-year-olds love collecting little treasures.

It’s a funny thing about nine-year-olds. You may look at your own nine-year-old and think: where did my baby go? Gone is the nine-MONTH-old who worried about approaching strangers and howled when you walked away. Now you have a nine-YEAR-old who may shoo you away when you drop her off at a friend’s house.

Yes, some nine-year-olds may seem embarrassed by their parents, yet they absolutely want you around on the sidelines. They want you to attend their sporting events or school concerts and to organize their birthday parties. Just try not to take it personally when they want to spend more time with friends.

Nine-year-olds can get a little stinky, even if puberty is years away for many of them. Be sure to let them know that their bodies will change gradually over time. Get them deodorant and remind them to use it. Talk to girls about periods because some start around 10 years of age.

Because of increased attention span and intellectual growth, nine-year-olds will reliably carry out chores and perform many self care tasks. Encourage them to be more self sufficient. You will be happy for the help and you will build your nine-year-old’s self-esteem. On the academic side, they read chapter books and often enjoy non-fiction books. At this age, they enjoy a variety of clubs, team activities, and hobbies.

Remember the basics:

-Eat: Teach basic nutrition

-Sleep: Most nine-year-olds need around 11 hours of sleep per night.

-Pee/poop: While nine-year-olds use the bathroom independently, occasionally ask your child if they are constipated, and ask if they try to “hold it” all day in school. If the answer to either one of these questions is yes, see our post on these topics.

-Love/guidance: Just like you did when they were toddlers, remember to praise your nine-year-old for positive behaviors such as saying “please” and “thank you” or for helping you clear the dinner table. Once they know that you approve, they will repeat those behaviors. Nine-year-olds are known for whining for long periods of time. Dr. Lai remembers her son whining about losing screen time. He would suddenly appear out of nowhere and whine two inches from her face wailing,”Why? Why? Why?” Watch out, if you give into a whining kid, even sometimes, you’ll end up encouraging their whining. Think slot machines— even though gamblers usually lose at slot machines, they continue to play them because SOMETIMES gamblers do win.

If you have not done so already, teach your nine-year-old to use a phone and teach them whom to call in an emergency. Some kids this age come home to an empty house for a little while until parents return from work. Review what you expect them to do while they are alone.

Reminder about car safety: Many should still be in booster seats because they are not yet 4 ft 9 inches tall. They should NOT sit in the front seat of a car; the back seat is still safer for them.

Nine-year-old kids are still part of the golden age of parenting— too old to take a nap, but too young to drive. Enjoy spending time with your nine-year-old doing things that interest both of you. Enjoy their enthusiasm and increased ability to understand higher concepts. Time spent with parents or other caregivers who enjoy them contributes to building their resilience.

Speaking of nine-year-olds, please celebrate with us NINE YEARS of Two Peds in a Pod®! We are enjoying the journey and hope that our advice can help build resilience and self-confidence in the parents we write for! Our best present from you is your continued presence.

Happy Ninth Birthday to your nine-year-old and to Two Peds in a Pod®!

Julie Kardos, MD and Naline Lai, MD

©2018 Two Peds in a Pod®

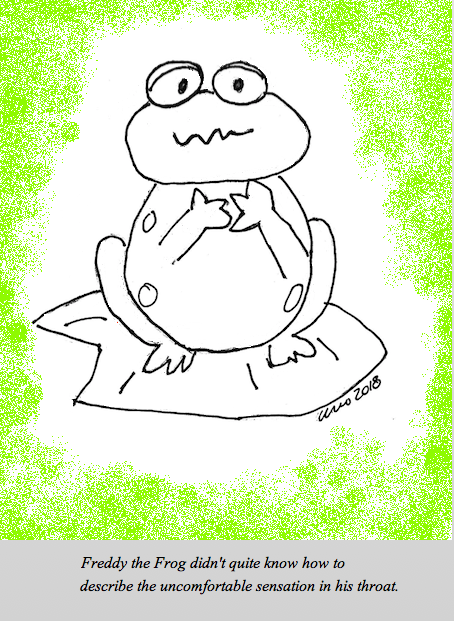

Does your kid spit out medicine? Clamp her jaws shut at the sight of the antibiotic bottle? Refuse to take pain medicine when she clearly has a bad headache or sore throat?

Does your kid spit out medicine? Clamp her jaws shut at the sight of the antibiotic bottle? Refuse to take pain medicine when she clearly has a bad headache or sore throat?